For the first time in human history, likely, I bought a Playboy Magazine STRICTLY for research. As a Nancy Drew scholar I find myself drawn to purchasing and reviewing any type of Nancy material I can get my hands on – including the July 1978 issue of Playboy “TV’s Nancy Drew Undraped.” I knew going into reading this that the issue was going to be centered on masculine sexuality – especially given Hugh Heffner’s views on sexual liberation for men- however I did not expect to see childhood photos of the “Playmate of the Month” next to her fully nude centerfold.

The centerfold in Playboy magazines can be seen as THE iconic symbol of the publication. This aspect of the magazine pictures a fully nude woman (the Playboy Bunny of the Month). Hannah Reagan, in “Playboy and Pornification: 65 Years of the Playboy Centerfold,” says that,

Whether the Playmate of the Month is the true “centerfold” of the magazine is debatable, as not every issue featured something clearly identifiable on the online database as a centerfold (that is, a full two page spread that crosses the “centerfold” with little or no text on the image). The vast majority of these images appear to be single page images, although in more recent years it is more common to find two-page or sometimes even three-page foldouts. (Reagan)

While the centerfolds do not have text, the pages accompanying them do. When opening to the centerfold, the left side of the page gives the reader a “sneak peek” to that month’s featured Playmate, while the right side gives a “data sheet” of the model in question. These sheets include not only the expected “data” on the Playmate (name, age, birthday) – but also their measurements (breast, waist, and hips), turn ons and turn offs, personality traits, and (as noted earlier) three “candid” photos.

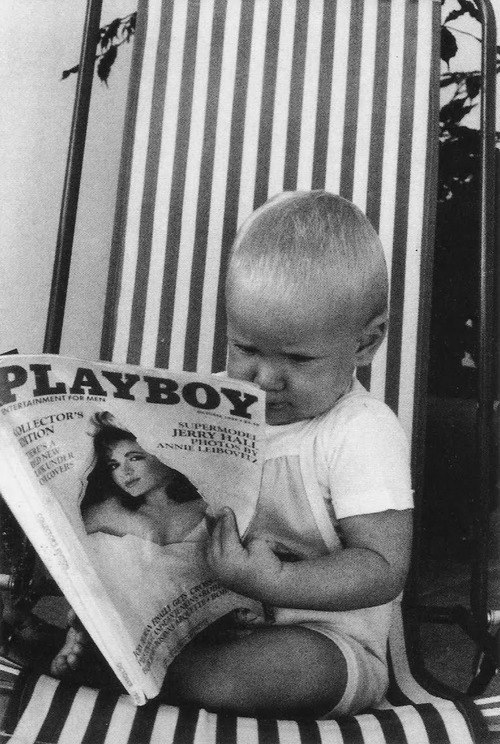

While in recent years these photos seem to focus more on expanding upon what is in the aforementioned data sheets, showcasing the models acting out the activities mentioned on the sheet, the past holds a different story. In the four issues I looked over in my (admittedly shallow) research (July 1978, March 1979, October 1981, and November 1998), the photos featured ranged from the youngest depicting the model at 11 months old to the oldest picturing the model at 18. The girls featured in the four magazines were 20-22 years old during their time as Playmate of the Month, meaning that the oldest of the “childhood” images of them were as recent as three years prior. While some photos pictured the Playmates with grandmothers or playing outside, others pictured them in bathtubs as a toddler of 11 months old (October 1981) or featured their school photos from elementary school at age 9 (July 1978). While the trend of featuring children in the “dirty” magazine seemed to be abandoned in the early 90s, it does appear to have been a staple of the Playmate of the Month data sheets 70s and 80s. This isn’t totally out of the blue for Playboy in that era (who notably featured nude photos of a then ten-year-old Brooke Sheilds in December of 1986), but it is still startling to see a juxtaposition of a sexualized, adult, nude model facing her childhood self. So why include childhood photos? What are the men getting from viewing not only the Playmate in the present, but also her past iterations?

As a sex focused magazine, Playboy of course caters to the male gaze – and consequently male loneliness. Peter Jackson, Nick Stevenson, and Kate Brooks write in Making Sense of Men’s Magazines that,

Magazines like Playboy were essential in promoting the belief that well-adjusted heterosexual men could avoid the commitments of conventional marriage for reasons other than homosexuality… despite pressures from… immediate family to get married and produce children and despite losing contact with married friends, a modern bachelor can expect emotional support from other single people (mostly women), nights out with their mates (mostly men), the time and money to indulge their hobbies and a string of casual affairs with younger women. (Jackson, Stevenson, Brooks 80-81)

The bachelor lifestyle that Playboy and similar magazines promote is one of a “free” man, no responsibilities, no money problems, no lack of willing bodies waiting for a chance to sleep with him. While this may seem like the dream life, one of no real responsibilities, there are also no real connections. His friends are for nights out, the women in his life are fleeting flings that may offer momentary connection but lack depth. The interactions between this bachelor rely not on true connections, but rather as transactional moments of intimacy that do not expand beyond a single night.

This lack of connection is what leads to the want and need to know the Playmates on a personal level. It is not enough to know their likes and dislikes, or what movies they enjoy, these bachelors crave the emotional connections they are unable to form in their real life. While the data sheets can be altered to fit a man’s fantasy of a woman who loves horse races and red Ferraris, but dislikes decisions and Reflecto Sunglasses (in the case of Karen Morton), the photos cannot be altered. Men, by viewing the images, are offered the chance to form a parasocial relationship with these women, one where they believe that they have some sort of “special” insider knowledge about the Playmate’s lives. They can view her past without the interference of the editors, making “stable” relationships with the reality of the naked woman and her past versus the presentation offered by the magazine.

This relationship is not only presented by Playboy, but actively encouraged by the publication. Carrie Pitzulo, in Bachelors and Bunnies: The Sexual Politics of Playboy writes that, “In the early sixties, the magazine shifted away from the antimarriage/antiwoman vitriol of its previous years and instead presented a more compassionate view that emphasized personal responsibility in romantic relationships” (Pitzulo 105). This shift not only saw a change in the types of articles that were published, but also how the readers were meant to engage with the women featured in the magazine. The Playmates were not simply tools used for pleasure, they had personalities and history that the viewer was not only meant to know but supposed to know. The photos of their childhood give not only an unedited and untouched view of the man’s sexual desires and want, but also allowed them the illusion of knowing the Playmate outside her sexual persona. While the Playboy bachelor could not afford real relationships in his personal life, he was allowed to find an imagined intimacy within the pages of the magazine.

I was hesitant, at first, to write this piece since blatant sexual imagery and writing is outside of my academic wheelhouse (I prefer to stay with the “virginal” girl detectives as Michael Cornelius labels them), but after thinking it through I realized that it was more of something I had to write about. Children’s literature, and its scholarship, has a strong focus on the presentation and perception of childhood (it’s something the discipline cannot escape). While the Playboy magazines are not something I really want to write about in the future (I can go the rest of my life without viewing another), as someone who wishes to cement her future in this field, I must investigate how childhood is seen through a variety of lenses and for a variety of means. Do I think that the Playboy editors were thinking of the portrayal childhood when they included toddler photos of the Playmates? No, but because these images focus on the Playmate’s childhood and how she lived at the time it is an expression of childhood nonetheless.

Citations

Image: Jean Rey Julien Rio De Janeiro Playboy Magazine Postcard

Marcus, Ken. “All in the Family.” Playboy, July 1978.

Pitzulo, Carrie. Bachelors and Bunnies: The Sexual Politics of Playboy. University of Chicago Press, 2011.

“Private Eyefull.” Playboy, Mar. 1979.

Regan, Hannah. “Playboy and pornification: 65 years of the playboy centerfold.” Sexuality & Culture, vol. 25, no. 3, 8 Jan. 2021, pp. 1058–1075, https://doi.org/10.1007/s12119- 020-09809-2.

Stevenson, Nick, et al. Making Sense of Men’s Magazines. Blackwell, 2001.

“Taylor Made.” Playboy, Nov. 1998.

“Toughing It.” Playboy, Oct. 1981.

Leave a comment